You’ve probably seen them all over town, nowadays feeling almost secreted into neighborhoods on once-busy corners. Despite the flamboyance of their cousins built by Schlitz and Pabst, former Miller tied houses often don’t have elaborate Queen Anne turrets or medieval castle-like rooflines. But you can still recognize them.

A tied house was a tavern with an exclusive relationship with a specific brewery to sell that brewer's products. Sometimes the taverns were owned by the brewery and leased to an operator and other times, brewers made tied house deals with independent tavernkeepers.

Before Prohibition wiped out the phenomenon, pretty much all breweries had some tied houses as a means of controlling distribution of their product.

There’s one that’s a bit fancier than normal on the corner of Holton and Reservoir (designed by Eugene Liebert, whose own home was next door – you can see it peeking out at left from behind the tied house in the photo above), but check out the one nearby on Garfield and Hubbard, pictured below.

That one, more modest, is your clue to finding a former Miller tied house: a bit of understated brick work, including some corbelling up top. Like the more elaborate one a few blocks away on Holton, this one has (or had) a Miller sunburst medallion above the entrance.

Despite the fact that Miller was by far the smallest of Milwaukee’s big four brewers at the dawn of the 20th century – producing fewer than 300,000 barrels in 1903, while Schlitz made more than a million and Blatz produced half a million barrels; in 1907, Pabst made more than 2 million barrels of beer – it was a big-time player in tied houses.

The Miller sunburst medallion is removed from a former tied house at 301 E. Garfield Ave.

The medallion is preserved in Miller's offices on Highland Boulevard.

The brewery had more than 1,000 of them in 18 states – though most were clustered in Wisconsin and nearby states – including places as far flung as Texas, Montana and Alabama.

They were in cities, in small towns and in rural areas. Miller had as many as six tied houses up in the town of Ashland. Lumberjacks, it seems, were thirsty for beer.

Many of these Miller tied houses survive. There’s one on Newhall and Belleview, for example, that’s no longer a tavern, and one nearby at Bartlett and Bradford.

Another building not far away on Bartlett and Irving, pictured above (you can see a different version of the medallion above the entry on this one), looks like a tied house but never was one.

A particularly handsome one is located in Cudahy.

Walter Choinski's tied house had a buffet and six lanes of bowling at 730 W. Mitchell St.

Walter Choinski's tied house had a buffet and six lanes of bowling at 730 W. Mitchell St.

There’s one on 2nd and Washington that’s home to Braise restaurant. Another is on 7th and Rogers. There’s one painted blue on Pierce and Clarke in Riverwest. These places were all over town. If you've ever closed Wolski's, you've closed a former Miller tied house, and if you ever tied one on at Judge's, you tied one on at a one-time Miller tied house.

Many were designed in the first years of the 20th century by the architectural firm of William Wolff and Joseph Ewens. The firm, with office above a Miller tied house on Water Street, also designed the nine-story Miller Hotel that stood on 3rd Street from 1917 until 1980.

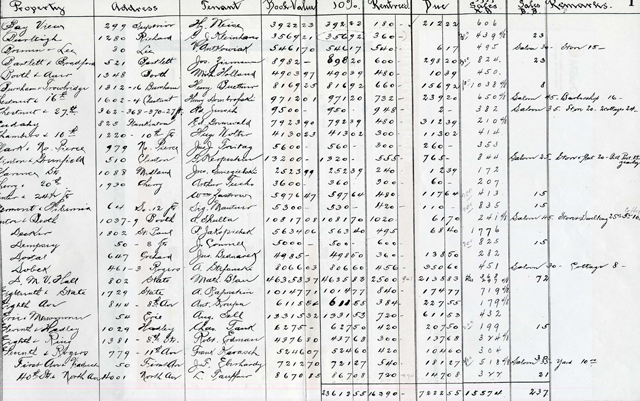

A 1917 Miller ledger shows five pages of tied houses in Milwaukee alone. Milwaukee history (and punk rock) fans will be interested to note that there’s a listing for a tied house called, "Norman Apts." at 620-30 Grand Ave.

Frederick J. Miller, who arrived in Milwaukee in 1855 and immediately became active in the brewing game, opened a saloon on the northwest corner of Water and Mason Streets by 1857.

Later, a tied house called the Miller Cafe occupied a three-story building on the site. That building survives, in an altered state, and was most recently home to Bruegger’s Bagels.

According to information provided by Miller’s staff historian Daniel Scholzen, "The saloon might have been included in Miller’s initial purchase of the Plank Road Brewery, but could also have been acquired in a separate transaction. Prior to the tied house system, it was common for brewers to operate taverns on or near brewery premises, as Frederick J. Miller did both in Germany and at the Plank Road Brewery beer garden. Miller probably did not operate the Water Street saloon for very long, and in general he preferred to do business with independent saloon keepers."

In his book, "Miller Time: A History of Miller Brewing Company, 1855-2005," John Gurda notes that there were seven or eight Miller tied houses in Milwaukee, including one on Jones Island, in the 1880s.

"Miller typically paid all license fees and taxes on his tied houses," Gurda writes, "handled routine maintenance (including privy-cleaning), and furnished the establishments from top to bottom."

Scholzen says that Miller took a utilitarian approach to the tied house system, willing to discuss any arrangement that could move the product. While the brewery owned some tied houses and leased them to operators, others were owned independently. Some were designed and built according to standardized designs (like the ones drawn by Wolff & Ewens) and others were retrofitted into existing bars or retail spaces.

While not typically elaborate on the outside, Miller’s tied houses paid attention to detail on the inside. In addition to Miller logos and signage, the chairs (the back of one is pictured just above) often had the Miller marque on them and the glassware was branded in a variety of styles, too.

Sometimes the furniture was loaned by Miller to the taverns, other times, the taverns owned the furniture after buying a specified amount of beer.

"(Miller) account books are sprinkled with expense items for iceboxes, counters, back bars, pool tables, brass rails, chairs and tables – purchased second-hand if possible. The brewer also produced advertising materials for his tied houses as well as his wholesale accounts – corner signs, lithographs, cards, calendars, and keg heads that have become coveted collector’s items."

In his research notes, Gurda offers an example of how all-encompassing the furnishings provided by the brewer could be. In 1900, Miller provided to a tavern in Chicago, "a 16-foot oak bar with brass foot rail and copper lined workboard, 16-foot back bar with large mirror, 6-foot bevel edge plate glass cigar case with counter, 15-foot chipped glass partitions with swing doors, 4 marble tables, 22 chairs, a 16-foot birch partition, and a pool table with balls, cues, rack, triangle, and bottle – plus lemon squeezer, cigar lighter, and ice pick."

The interior of the Angeles Buffet, a Miller tied house in Fort Worth, Texas.

In 1910, Scholzen notes, Miller’s assets in saloon furniture and fixtures totaled $813,366. Just four years later, these assets rose to $912,686.55.

Tied houses were worth the investment to brewers like Miller, says, Scholzen, because it meant they didn’t have to vie for position among independent tavernkeepers. It also improved their profit margins and allowed them tighter control of the distribution chain.

But the system was a complex one that came with a wide variety of issues, in addition to the expenses Gurda outlines above. Scholzen points out that, despite its system of regional and local account managers it was often difficult for Miller to prevent a tied house from selling competing products.

And in "Miller Time," Gurda tells the story of one tied house manager who often got so drunk he could not "properly attend to the business entrusted to him by Frederick Miller."

While Fred Miller wasn’t eager to buy taverns himself, his sons Ernest and Fred Jr. led the company’s tied-house boom and it was during this time that Miller became such a market force in tied houses. And when first Prohibition, and then the Depression, hit, it was this move that helped cement Miller’s survival.

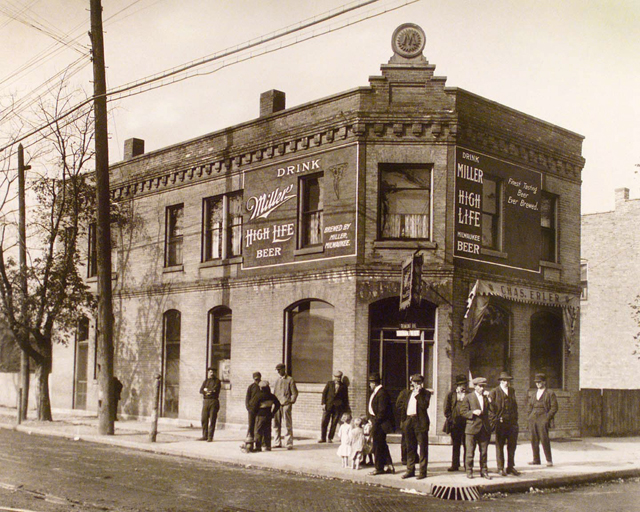

Charles Erler's corner tap, likely in Kenosha, is a perfect example of the "prototypical" Miller tied house.

"Brewers could see Prohibition coming from a mile away," Scholzen says, noting that as more and more counties and entire states went dry, the writing was on the tavern wall.

When Prohibition arrived in 1920, tied houses were converted to candy stores, soda fountains, barber shops and dime stores. Like all breweries, Miller retooled its product line, launching Heart-O-Barley Malt Syrup, Verifine Lemon Soda, High Life Pure Tonic Beverage and others.

According to a post on the company’s website, "Despite the company’s best efforts, there weren’t any successful markets for these products. Things got so bad that Miller Brewing was put up for sale in 1925 (no one bought it, thankfully)."

Along with some other sound investments, real estate – which the brewery spun off into a separate business – helped the company survive. In addition to taverns, Miller owned hotels, apartment buildings and theaters.

By the time the beer began to flow again in 1933, the 21st Amendment granted wide-ranging alcohol regulatory powers to the states and the tied house system was finished.

"The implications of the new order were not lost on America’s brewers, especially those, like Miller, who had built their prosperity on a foundation of tied houses," writes Gurda in "Miller Time."

"There was a massive sell-off of retail properties that hadn’t been liquidated during Prohibition. The brewers were forced, in a sense, to start over, and they found other ways to compete for territory."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He can be heard weekly on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories.