If you like this article, read more about Milwaukee-area history and architecture in the hundreds of other similar articles in the Urban Spelunking series here.

We're re-sharing this 2020 story because the venue is featured in the inaugural West Bend Doors Open event this weekend, which you can read about here.

With all due respect to the striking Museum of Wisconsin Art and the many residential and commercial treasures that make West Bend a great place to geek out on architecture, it is the 1889 Washington County Courthouse, perched atop its hill at 320 S. 5th Ave., that is the true gem of the county seat.

Standing regally on its high ground, all cream city brick and red roof, its tower soaring nearly 150 feet above the town below, this building, reportedly designed by Milwaukee architect Henry C. Koch, is a stunner.

It ceased operation as a courthouse in 1962 and after a number of other civil uses, the three-story building has, for the past nearly 30 years, been home to the Washington County Historical Society and the Old Courthouse Museum, which recently reopened after a pandemic shutdown, with a new branding as the Tower Heritage Center – which also includes the interesting and beautiful jailhouse next door – and a new executive director, who arrives from no less than George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

But more on that later.

First, thanks to the photo of Henry hanging in the lobby (above), I always assumed the building to be by the same architect that designed Milwaukee’s City Hall and similarly styled Richardsonian Romanesque courthouses around the upper Midwest. But then I did some digging, which, as is sometimes the case, just made things murkier.

The smaller and slightly older jail and sheriff’s residence next door was clearly designed by Milwaukee’s Edward V. Koch (no relation). On this everyone seems to agree and the Tower Heritage Center has some of the jailhouse blueprints signed by Edward, who had also designed a poorhouse at the same time as the jail. That building, at a different site in West Bend, has been razed.

But some sources seem to suggest Edward also designed the courthouse, though I could find no solid evidence of that in the newspapers of the day. However, neither could I find proof that Henry designed it, either, although reputable sources like Russell Zimmermann’s "Heritage Guidebook," give the nod to Henry.

And so does Janean Mollet-Van Beckum, The Tower Heritage Center’s Curator of Collections and Exhibits, who showed me around one day, along with new Executive Director Steve Stuckey. Though there’s still a little uncertainty.

"I was unable to find our former Curator of Education’s notes on the topic," Beckum tells me. "She left three years ago and many of her files went with her. I know she found it and was excited to find definitive proof because there had been confusion around it for years. She spent several months researching the buildings in preparation for our architecture tours."

That former employee, Jessica Sawinski Couch led the tours and shared such interesting data as the top of the tower is only about 50 lower than nearby Holy Hill and there are 131 steps between the basement and the tower’s sixth floor (some of them are pictured above).

She would also tell folks that the dazzling maroon, gray, black and off-white terra cotta in the lobby (pictured above) were made in northern France, that the weather vane atop the tower is 11 and a half feet tall and a bit about the Lady Justice panel on the building’s north facade.

It was the work of Belgian-born terra cotta artist Henri Plasschaert, who taught at the University of Pennsylvania and helmed the Decorative Sculpture Department at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s school.

Beyond the architect, the building shares other connections with Milwaukee.

The square was donated to Washington County in 1853 for its perpetual use by Byron Kilbourn, James Kneeland, William Wightman and Erastus B. Wolcott – some important names in Cream City history.

Two views of the main staircase.

A previous courthouse that had stood on the site was moved to Main Street when the current structure was built and used for a time as a hardware store, though it has now long since been razed.

Inside, we walk through the building, starting of course in the lobby, which is so rich in decoration and beautiful finishes that one could spend hours gazing at it all. The fact that some historical photos of the building hang on the walls helps, too.

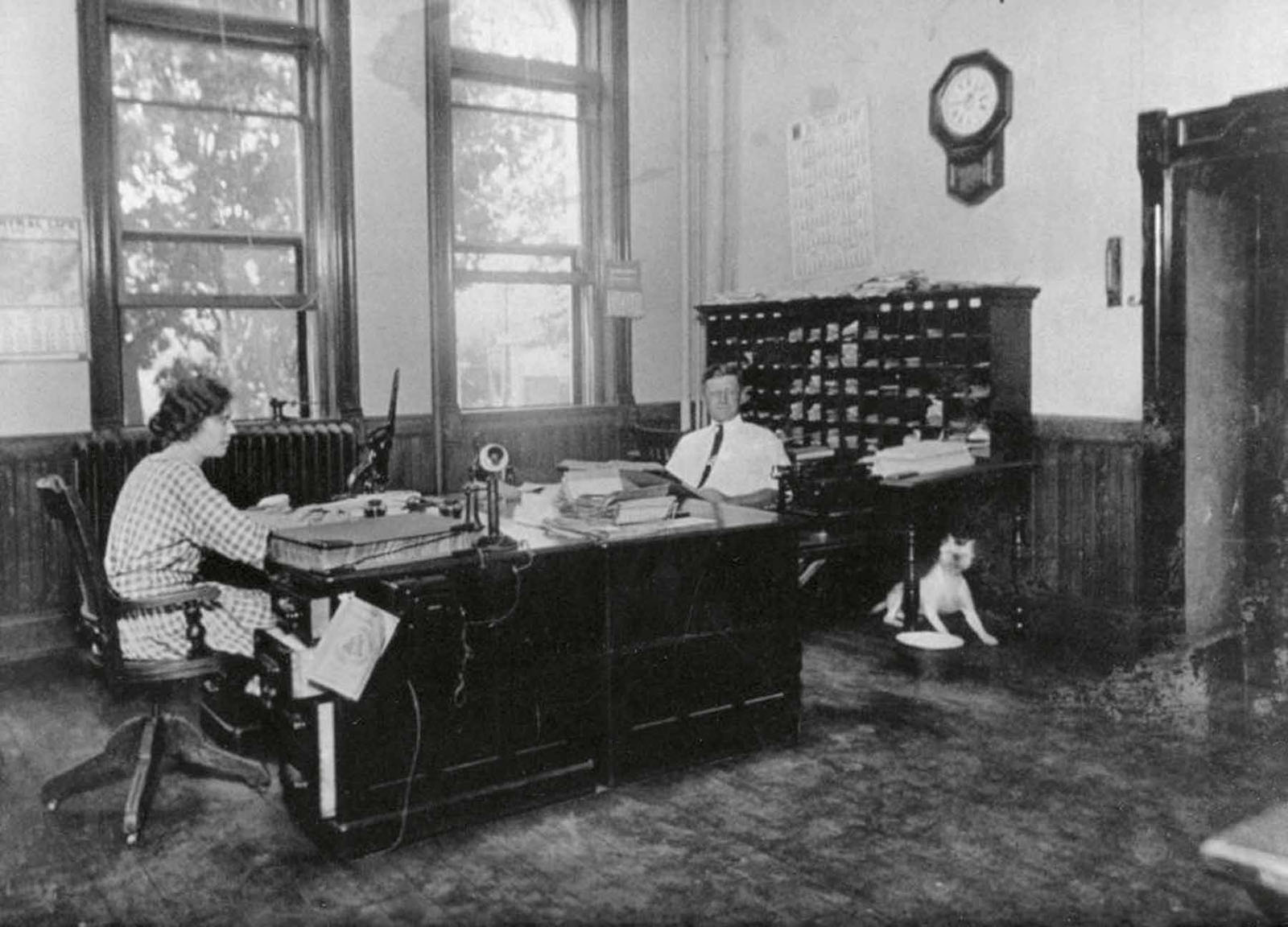

An interior shot from the 1920s. (PHOTO: Courtesy of Tower Heritage Center)

We check out the various former offices with their tall slender windows and their surviving painted signs on the door glass and then head upstairs to the large courtroom, which has a soaring ceiling that creates a truly impressive space. Remarkably, for decades, that was invisible to most as a dropped ceiling had been added at some point. It is now, thankfully, gone.

The judges chambers and other offices boast fireplaces, and the whole place is dotted with display cases with objects and information that tell the story of Washington County. In one room there is also the jaw-dropping Zinn dollhouse (which I mention in this story), that you must visit someday.

For now I’ll just say that it was such a labor of love that its builder, malt maven Walter Zinn, not only made a tiny loom for a sewing room in the dollhouse, it was a functioning loom and he – most improbably – used it to create the fabrics in the dollhouse.

Up in the tower, there are numerous levels and many of them contain the scrawled signatures, often dating to the 19th and early 20th century. The view gets better and better as we climb and when we get to the level that has a balcony, we step outside for a breathtaking view in all directions, over the town and out into the countryside.

We climb a ladder to another dark level and then consider another much taller ladder that ascends nearly straight up into the darkness and leading ultimately to the three wee windows you can see almost at the tip top of the tower. We decide to wait for another time.

But up here on the balcony, Stuckey – who is from St. Louis – tells me he’s excited to be in Wisconsin with his family. His wife’s a Wisconsin native, so they know all about what to expect when winter arrives.

Peering down, we get an ace view of the jail and we decide to go check it out.

As stunning as Henry’s courthouse, though on a much smaller scale, Edward’s jail has gorgeous masonry on the outside and some really interesting features inside.

The front of the building, which dates to 1886, was a residence for the elected sheriff and his family during each two-year term and there are parlors on the first floor, a kitchen in the basement and bedrooms upstairs.

But in back was the jail, where the prisoners were fed by the sheriff’s wife and where they often played games with the sheriff’s family. Most, of course, were not violent offenders and would’ve been townspeople they likely knew.

The cells and the whole space are caged and there are some interesting touches, like an opening from the residence that served as a megaphone and spy hole into the cells, and a mechanism for locking and unlocking all the cell doors at once.

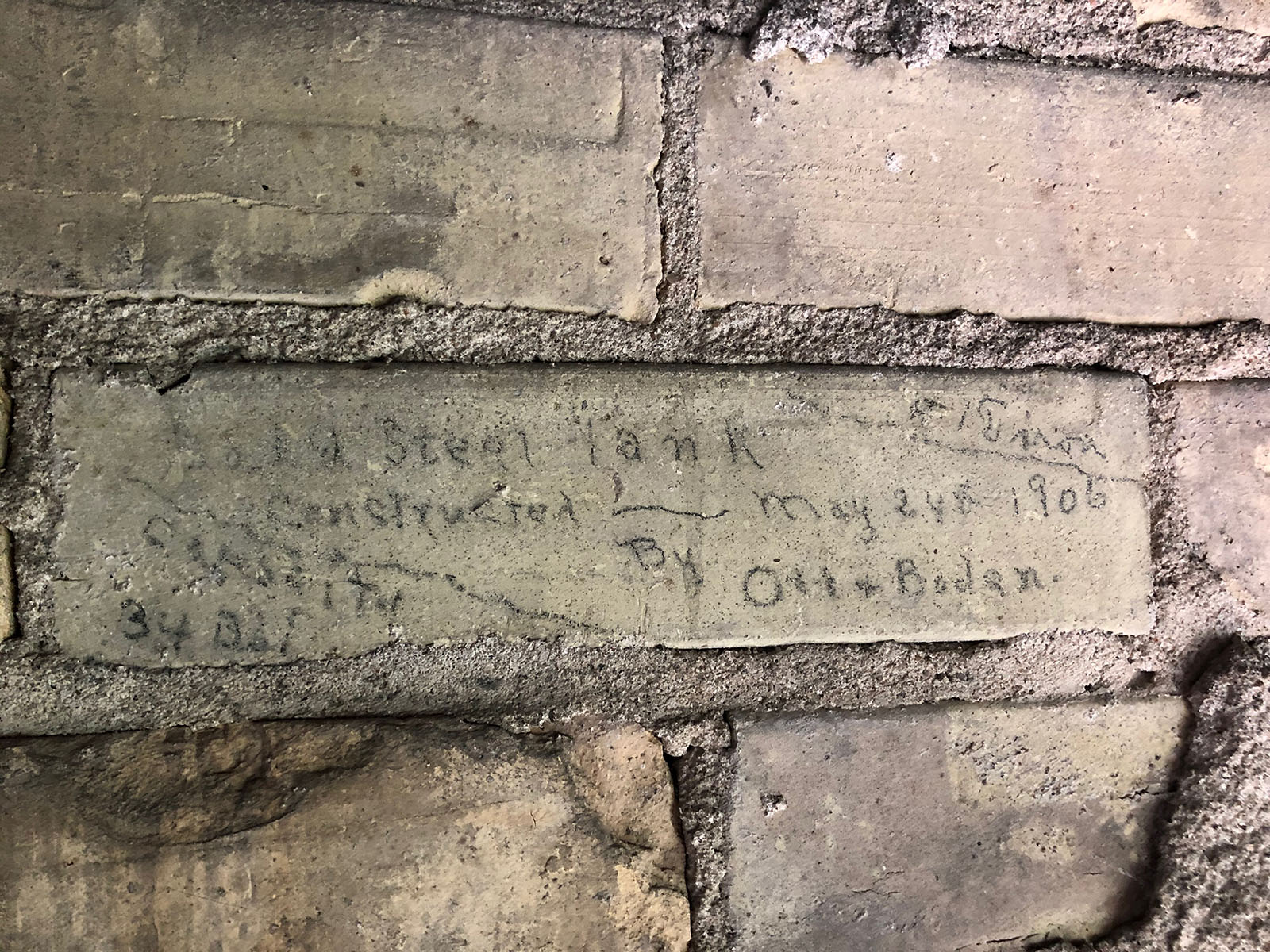

Up in the attic, we see two chimneys that merge into one, which is not a common site around here, and a freshwater cistern, which would collect water from the gutters for use in the house, survives up there.

Nearby, on a cream city brick, in pencil, workers noted the date the cistern was installed. It is signed Ott & Boden, the name of the hardware store that occupied the former courthouse after it had been moved to Main Street, according to Beckum.

According to the Milwaukee Journal in 1886, the High Victorian Italianate jail cost about $19,000 and, "although small, will be the model one of the state when completed."

It, too, is now part of the Tower Heritage Center, filled with period furniture and objects to show visitors how it would’ve looked in its early days.

And now, as I mentioned earlier, the center has reopened to the public with its new name and new director, but with the same interesting exhibits in the same absolutely stunning buildings ... but with safety measures like social distancing, masks and hand sanitizer.

"We know our guests are looking for opportunities to get out and spend time with their families this summer, and we’re confident we can deliver that," says Stuckey.

"We take the safety of our staff and patrons very seriously, and we will continue to monitor our operations to make sure we’re providing the best and safest experience for everyone."

For more information on admission, opening hours, events and more, visit historyisfun.com or call (262) 335-4678.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He can be heard weekly on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories.